Executive Brief No. 59

1. The importance of private investment in Europe

The qualitative impact of private space investment in Europe is difficult to estimate, however much of the European New Space Ecosystem has either relied on private investments or is expected to rely on it in the future. Private investments no longer only supplement public budgets but rather have become complementary to them. The ratio of private space investments to public space budgets has quickly grown, reaching 20% in the United States and 17% in Europe in 2021. While the comparison holds limitations, notably as public budgets represent a demand for space infrastructure and services, it highlights how critical private investments have become to the New Space ecosystem in Europe and how much the public sector and private investment increasingly work hand in hand to stimulate the growth of European New Space start-ups.

Private space investment in Europe has seen a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of close to 60% since 2014. European space start-ups have raised a total of €1.9 billion (not including OneWeb) to date pushing the European ecosystem at the forefront of the New Space “revolution”. European institutions and national organisations have taken an interest in this growth and have developed a range of investment mechanisms throughout Europe and throughout the space value chain with efforts and support structures now reaching billions of euros. This sustained backing and investment has allowed European New Space companies to grow, with the most successful of them winning breakthrough contracts with ESA and national organisations, allowing start-ups to begin bridging the gap with primes and LSI’s.

This development has occurred during a sustained period of global market growth which has permeated public and private markets throughout all verticals with a particular focus on deep technologies and SaaS. The growth in European space start-ups has been mostly driven by private investments, allowing companies to hire, create proofs of concept and sustain their R&D. However, few of these companies are cash flow positive and are yet capable of relying on market demand (B2C, B2B or B2G) to survive and grow sustainably. As such, many of the start-ups that received large amounts of capital did so at very high valuations, based on future growth and, at times, unclear business models.

2. Is the European New Space model at risk?

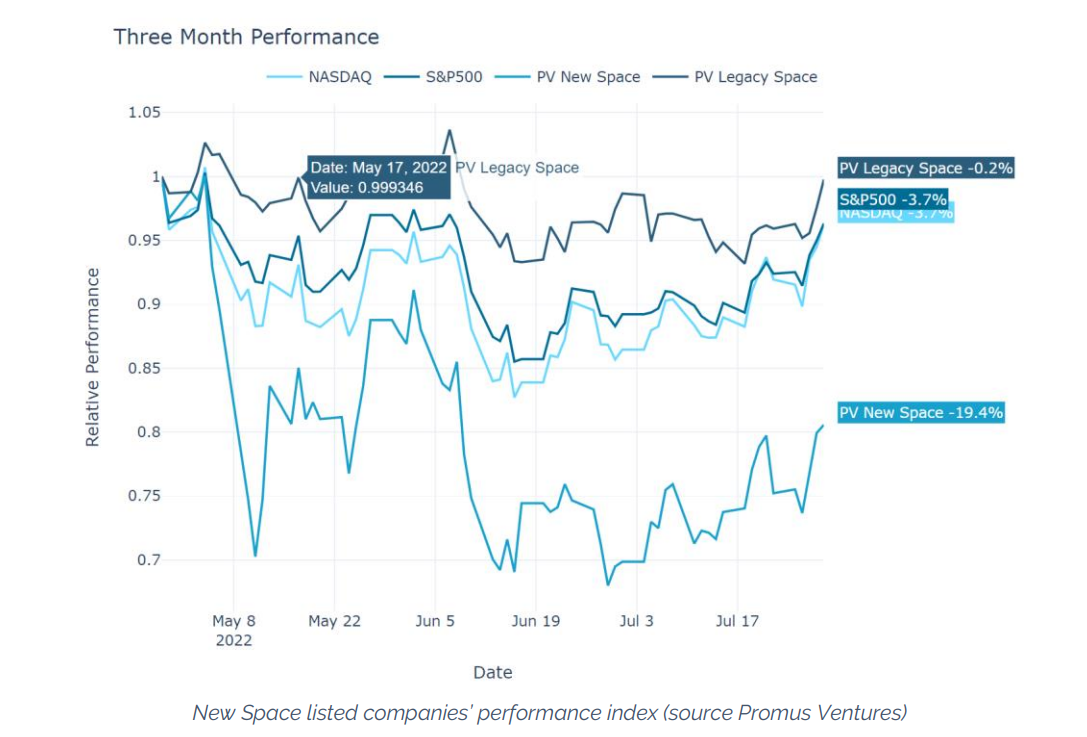

Recently, market conditions have soured. A combination of supply chain shortages, worldwide inflation, geopolitical tensions and an aggressive rise in interest rates are combining to make even the most bullish of investors fear a recession. These macroeconomic factors are likely to play an increasing role in the way investors distribute their investments. With private markets often lagging public markets, investors are now expecting to witness a slowdown in private investments with VC’s increasingly likely to step back from risky business models that remain far from revenue.

To keep up with the levels of investment seen in 2021, space start-ups in 2022 and 2023 will have to convince investors that their business models and profitability goals are still attainable. The underwhelming success of recent space sector SPAC listings will not help in assuaging investor fears and may affect their risk tolerance for the space sector as a whole. Most investors expect a domino effect in which valuations and funding are to significantly decrease from pre-IPO to series A, meaning that companies raising funds in 2022 or 2023 may have to raise at a flat or even lower valuation than their previous round.

European New Space companies have raised nowhere near as much capital as in the United States. Most rounds in Europe have ranged from pre-seed to series B and only a single series C has been registered so far. This means that the average European space start-up runway is expected to last a year, maybe two. Additionally, there are also some structural differences that make the European space sector more at risk. Beyond the differences in funding rounds, a history of anchor tenancy from the US governmental sector (NASA, DOD etc.) means that U.S companies can sign large scale and long-term contracts which in turn, can be leveraged to further foster appetite from private investors in the US, even during a protracted economic downturn.

One of the major risks for space startups originates from their business models. Until now much has been seen on the New Space offer side, but significant and diversified demand, both from government and private customers has yet to materialise. In line with this, a key factor underlining the fragility of New Space companies in Europe but also worldwide is that many of their business models only succeed when other complementary models are already in place. This is more commonly known as circular dependency and makes start-ups much more susceptible and vulnerable to suffer a chain reaction of failures. This is particularly true for upstream, high CapEx companies which have a long-term return on investment perspective and as such remain far from revenue. Downstream companies may be less risk susceptible. It is understood that only the startups able to pivot from investment-supported growth to business-supported growth will survive.

An example of how this risk permeates space business models is the use of bookings. Bookings are the value of contracts that customers have signed and committed to pay in the future. These bookings are used as a proxy for future growth, however, in the case of the New Space ecosystem, these bookings are often from other start-ups which also need to raise consequent amounts of capital to fulfill their contracts. This can lead to what is called stacked speculation and it can be very risky in a recessionary economy.

What to expect

While a slowdown of investment is likely, the strong level of funding seen over the past decade means that an overnight failure of space start-ups is improbable. However, some indicators are already foreshadowing a slowdown of investments. Private investors are increasingly focusing on their existing portfolio rather than seeking new investments and have highlighted a decrease of new market entrants. Should this slowdown continue or even worsen and based on the runway of start-ups, initial layoffs, company re-structuring and aggressive cost cutting can be expected to set in by end of 2022, and 2023 may see the first companies going out of business or failing to raise new capital.

Should there be a widespread market correction or a bubble burst, it is not necessarily seen as a bad thing by many investors as it will allow the most efficient business models and credible paths to revenue to survive, concentrating talent and capital in the most capable companies. Furthermore, investors see this as a land of opportunity as it will allow them to invest at much cheaper valuations. There is also a lot of new capital available for VC’s (dry powder), with 42 new funds and 6.1 billion of fresh capital available in Europe just in Q2 2022. In addition, slowdown effects of VC investment in European New Space may not become fully visible before 2023 as Q1 2022 was the most successful quarter for the European space ecosystem ever

3. The critical role of the European public sector

All is not doom and gloom. The space sector is of strategic value to the public sector and holds important considerations regarding the future of European strategic autonomy. As such, a decrease in public support appears to be unlikely. With many European space start-ups entering the “valley of death” and with companies increasingly struggling with their runway, it can be expected that the public sector will be stepping in to support space start-ups deemed of strategic value. This will be growingly important as it will ensure the leveraging of commercial space to ensure that innovation does not slip through the cracks of a recession. A recent case of a public institution stepping in for strategic considerations could be the example of the UK government with OneWeb.

In addition to strategic and sovereign considerations, it is also important to remember that public actors are themselves dependent on private space actors to provide them with industrial capabilities to fulfill national and pan-European needs as well as to safeguard economic continuity.

Beyond the intrinsic role of European New Space, the dependence on private investments is not as one sided as one may think. European and national Institutions have been continuously developing financial instruments to foster entrepreneurship and accelerate investment into space start-ups.

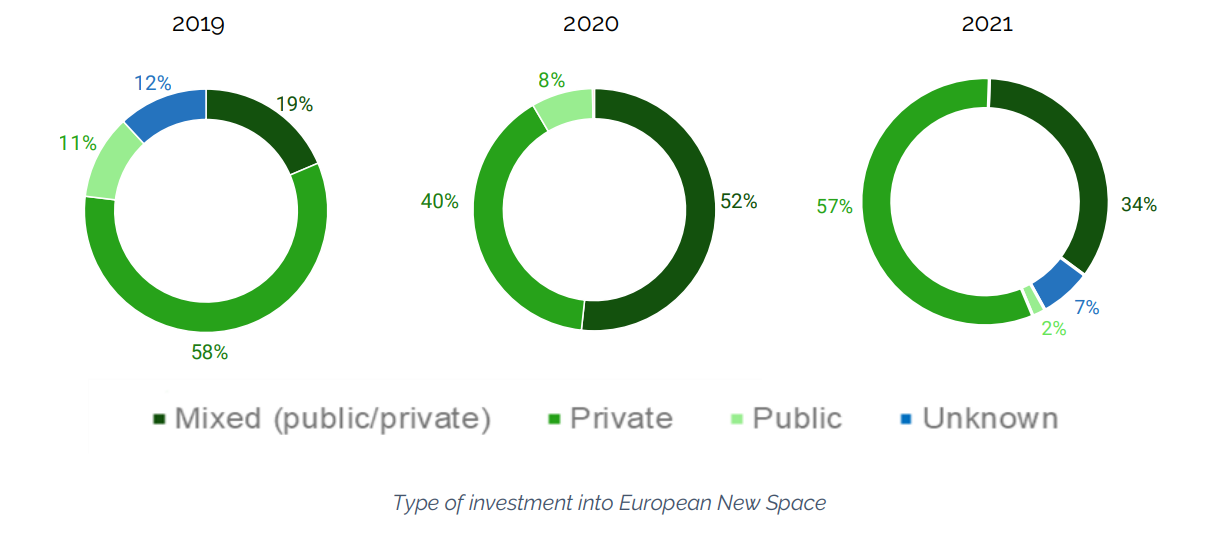

This has been very noticeable at early stages of the start-up development phase. The ESPI Space Venture Europe report quantifies the financial support of the public sector to the New Space ecosystem in Europe and points out that in 2020 and 2021, 52% and 34% respectively of the entire volume of investments into space start-ups came form a mixed consortium (public/private). This is critical as a majority of space start-ups highlight that public investment and contracts are often seen a pre-condition to private investments.

Key challenges remain

As previously mentioned, most space start-ups in Europe remain at early stages of their commercialisation phase and are in the so called “valley of death”. Should public and private market headwinds intensify, it could signify going out of business for many of these companies. Furthermore, with a lack of large scale and long-term contracts in Europe, and with no change of such status-quo in sight, relying on investments may be the only way to keep on growing for many early-stage actors. Consequently, supporting the scale-up of these companies through increased direct/indirect investments is key to protecting the European space ecosystem.

With investment in space companies being inherently risky, the capacity and willingness of public actors to “risk” taxpayer money in uncertain business models is likely to become increasingly scrutinised. As such, questions can be raised as to who the best suited organisation for direct investments is. The recent delays in funding by the European Innovation Accelerator were notably caused by an incapacity to manage equity financing and stakes in invested companies. As a result, figuring out the appropriate body (public or private) to support breakthrough innovation and to protect European space start-ups by supporting them throughout their commercialisation phase will be a key challenge over the next couple of years.

European private space investments have grown tremendously, reaching €611.5 million in 2021 (not including OneWeb) at an average CAGR of close to 60% since 2014. European institutional space budgets on the other hand have seen marginal growth. Should public budgets aim to keep on working hand in hand with private capital, a necessary scaling of public budgets is required to be capable of supporting New Space actors. The up-and-coming budget lines and notably the new ESA budget that will be announced at the Ministerial Council in November will highlight the Member States willingness to grow or not their support to the European New Space ecosystem and will provide an insight into the potential risks that start-ups will face over the next few years.

Finally, t0 ensure the European space sector resiliency, the EU, ESA and Member States will have to rapidly decide on the right transversal course of action to support the New Space ecosystem. As such, European actors could benefit in using a dedicated organisation, in similar fashion to the United-States “Office for Space Commerce”, to better structure public action and decision making when it comes to space.